Jane Stanford paved the way for a cohort of pioneering women

The earliest Stanford women were pioneers of their time, embodying an independent and trailblazing spirit nurtured in part by a university that welcomed women from the start.

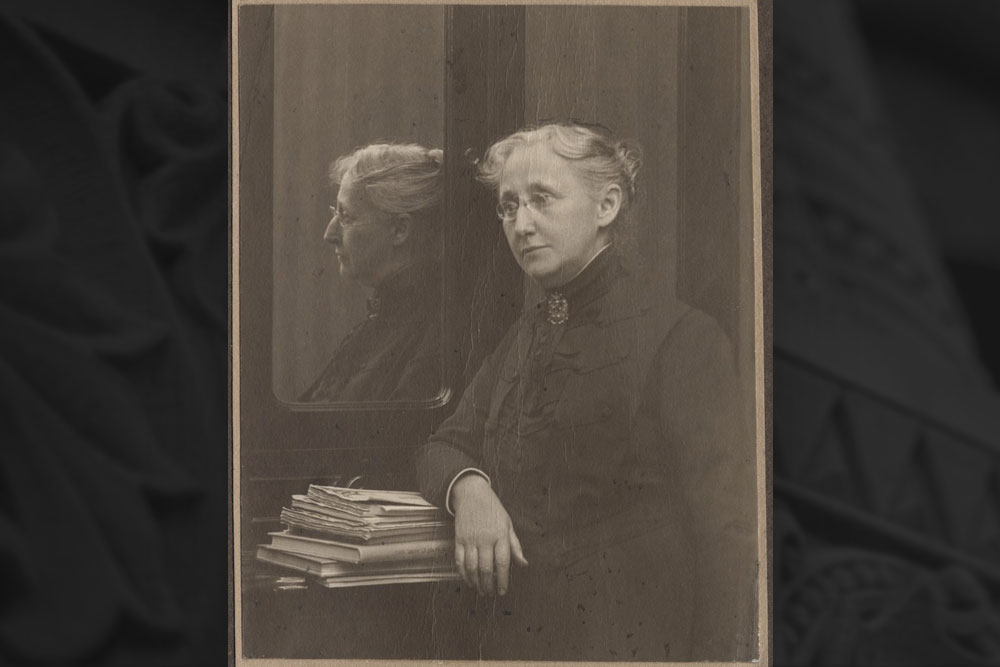

The iron-willed Jane Lathrop Stanford set an admirable example. University founder, administrator and world traveler, Mrs. Stanford was an accomplished and forward-thinking woman.

Together with her husband, Leland, she insisted on admitting women to the first student body. Moreover, all courses and majors, including the sciences, were open to women. As a result, nearly 25 percent of women in Stanford’s early classes majored in a scientific discipline. At the time only 4 percent of undergraduate women nationally pursued science, according to a Stanford Historical Society article on the period.

Jane Stanford also extended her support of women to the public sphere. Undeterred by objections from her husband’s railroad associates, she gave free rail passes to Susan B. Anthony and other suffragists on campaign in the summer and fall of 1896.

Trailblazing early female graduates

In 1891 Stanford was one of a few private co-educational universities. It was also one of the first institutions to offer advanced degrees to women from the beginning. On opening day, women held 130 of the 555 places in the student body, and in 1896 two women were awarded doctorates: Kathryne Janette Wilson and Mary Roberts Smith.

Many of the women from Stanford’s early classes went on to distinguished careers in academia, medicine and education, including Smith, who later became a member of the Sociology faculty.

Nettie Maria Stevens, ’99, majored in physiology and later conducted groundbreaking and historically significant genetics research that linked chromosomes to the determination of an organism’s gender.

Early in her career, Stevens spent four summers as an investigator at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station and six months in Italy at Naples Zoological Station. She continued her research as an associate in experimental morphology at Bryn Mawr College and wrote and illustrated more than 40 academic publications.

In his autobiography, David Starr Jordan – Stanford president and accomplished ichthyologist – described Stevens as “one of the ablest scientific investigators developed at Stanford.”

Anne Martin, ’96, a talented athlete, historian and activist, organized the movement that won women’s suffrage in Nevada in 1914. She was an 1895 intercollegiate women’s singles tennis champion and later a professor of history at the University of Nevada. Her work in the suffrage movement inspired young women across the country.

Lou Henry, ’98, was the first Stanford woman to graduate with a degree in geology. She collaborated with her husband Herbert Hoover, ’95 – geologist and future 31st president of the United States – on reports for his job as a mining engineer in China. From 1900 to 1914 the Hoovers lived in London, where Lou Henry Hoover helped organize and lead several organizations including the American Women’s War Relief Fund and Hospital and the Commission for Relief in Belgium. After moving to Washington, D.C., she was instrumental in establishing the Girl Scouts at the national and local level.

The Hoovers had always planned to return to Stanford and in preparation built a home using Lou Hoover’s singular design. After his wife’s death in 1944, Herbert Hoover donated the home to Stanford, where it serves as the president’s residence.

Pioneering faculty women

Pioneers in an academic world dominated by men, Stanford’s first female faculty members numbered just six throughout the university’s first decade.

Mary Sheldon Barnes, assistant professor of history, was the first, and only, woman appointed to the faculty when the university opened in 1891. Her Western American history course drew large numbers of students for its work in the field documenting local Native American and Hispanic heritage. She is best known for pioneering a primary source methodology for teaching history.

Women later joined the faculty in fields ranging from bionomics and physiology to English and German.

Psychologist Lillien Martin arrived in 1899 after study and research in Germany. An accomplished scholar, who originally trained as a physicist, she became a full professor of psychology in 1911. She was also the first woman to be appointed a department head at Stanford.

Clelia Duel Mosher, ’93, earned a medical degree from Johns Hopkins and returned to Stanford in 1900 as professor of personal hygiene and women’s medical adviser. Fifty years before Kinsey, Mosher embarked on a long-term research survey of 45 women. Her landmark studies of women’s health and sexuality are unique in the medical history and literature of the time.

Two beloved professors, Mary Yost and Edith Mirrielees, served the university well into the 20th century.

Mary Yost’s career as dean of women and associate professor of English was distinguished by her steadfast concern for the welfare of students. Arriving in 1921 from Vassar, she guided the university through a period of increased student enrollment and was active nationally in women’s education. When she retired in 1946, her campus home became a gathering place for Stanford women.

Edith Mirrielees, ’07, served on the English faculty from 1909 to 1944 and taught at the Bread Loaf School of English and at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont. Her text, The Story Writer, is recognized for its excellence in teaching creative writing.

Her service extended to the Stanford Red Cross unit in France during World War I, and she maintained an advisory relationship with the Bureau of Indian Affairs for 25 years.

In 1962, some 40 years after taking Edith Mirrielees’ creative writing class, John Steinbeck wrote a letter to his former professor. In it he captures her great gift for teaching the essential truths of writing and becoming a writer: “But surely you were right about one thing, Edith. It took a long time – a very long time. And it is still going on and it has never got easier. You told me it wouldn’t.”

Yost and Mirrielees are commemorated on campus in dormitories named in their honor. Mirrielees House was built in 1972 and was originally part of Escondido Village. Completed in 1982, Yost House is located in Governor’s Corner.