Imagination flourishes in Stanford’s Creative Writing Program

“Minds grow by contact with other minds. The bigger the better, as clouds grow toward thunder by rubbing together.” — Wallace Stegner

The novelist Wallace Stegner came to Stanford in 1946 to teach writing. He found a campus swollen with returning GIs and war workers. This cohort – later known as the Greatest Generation – had interesting stories to tell. At Stanford, Stegner developed a program of workshops, community and freedom to write that would nurture these writers’ talents and those of generations to come.

The Stegner Fellowships, as Stanford’s two-year writers’ fellowships are now called, are perhaps the best-known facet of Stanford’s Creative Writing Program. Stegner Fellows have gone on to become Pulitzer Prize winners (N. Scott Momaday, Larry McMurtry, Adam Johnson), poets laureate of the United States (Robert Pinsky, Philip Levine) and bestselling novelists (Scott Turow). Diverse in origin, they have brought new understanding of their own countries and cultures through literature (NoViolet Bulawayo). Many have returned to Stanford to teach new generations (Johnson, Kenneth Fields, Tobias Wolff).

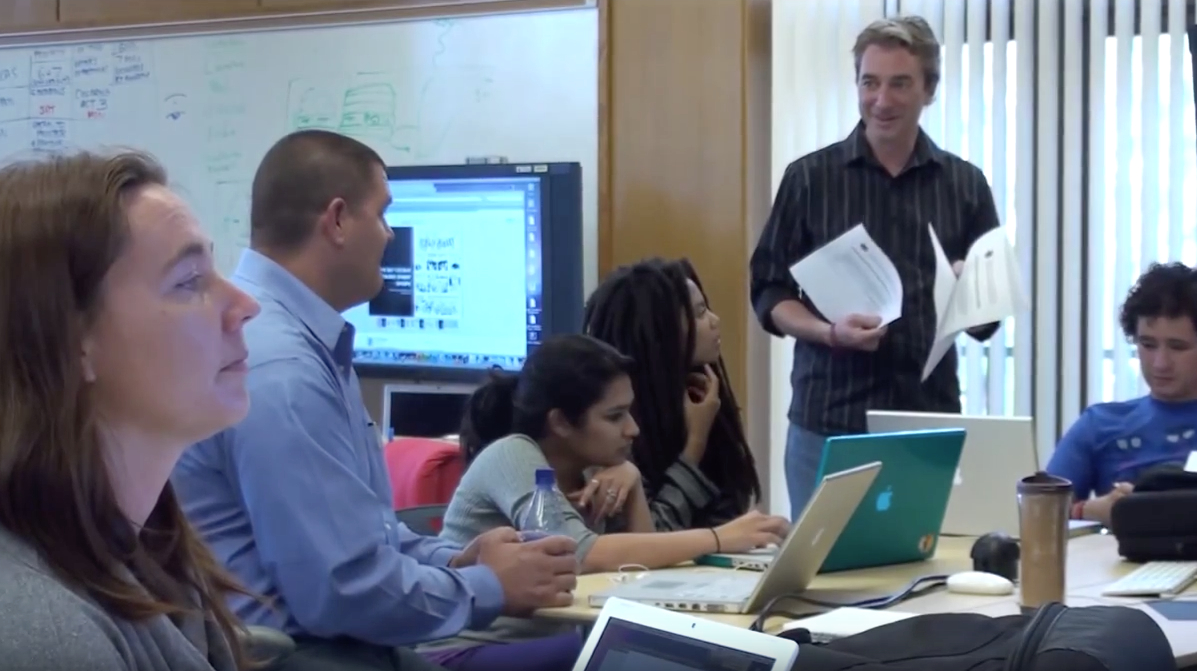

The milieu in which the Stegner Fellows flourish also nourishes the creative gifts of hundreds of Stanford undergraduates each year. Creative writing workshops and tutorials are among Stanford’s most sought-after courses. That’s unsurprising when one considers the value that Stanford puts on output, on expressing one’s ideas.

“We hated the idea that someone would come to this great university and think it’s either/or — ‘I’m going to be a science student, or I’m going to be a creative writer.’ We made the minor so people would know they didn’t have to make that choice.”

— Eavan Boland, director of the Stanford Creative Writing Program

“It’s the art of imagination. It’s a muscle that students want to activate,” explained Tom Kealey, a lecturer in the Creative Writing Program.

Nearly all of Stanford’s creative writing courses are open to undergraduates across the curriculum, though some, like the one-on-one Levinthal Tutorials, require a manuscript review. Nearly 70 percent of Stanford’s English majors have emphases in creative writing, whether in poetry or prose. There is also a creative writing minor. Its new Fiction into Film option culminates in the Hoffs-Roach Tutorial, in which students complete a 100-page screenplay. Another popular option is to take four or five writing courses as an informal emphasis.

The creative nonfiction courses are popular with students in the sciences, Kealey said: “Many want to make sense of their lives by creating narratives.”

Lectures about the craft of writing are also very popular. Professor Elizabeth Tallent teaches a course each spring, Development of the Short Story, that can attract up to 100 students.

The newest member of the program’s distinguished faculty is novelist Chang-Rae Lee, who comes to Stanford in fall 2016.

Informal workshops such as Poets’ House and Art of Writing offer an introduction to creative writing across disciplines. Innovative courses seek to explore new literary forms and to bring appreciation of writing to more people in new ways.

Stanford’s creative writing program was the first to offer a course in completing a graphic novel, a popular class repeated every other year. It gives undergraduate awards for environmental writing, an important aspect of Wallace Stegner’s legacy.

In spring 2015, program director Eavan Boland led a free online course on Ten Premodern Poems by Women that drew more than 1,000 participants from 105 countries. For the course, the office of the Vice Provost of Teaching and Learning enhanced Stanford’s OpenEdX platform to allow participants to submit narrative responses and even poems, an innovation that will help future online humanities courses.

Watch the creation of the Creative Writing Program’s latest graphic novel in this video.